|

![]()

|

|

Washington Rowing: The 1936 Olympic Team

![]()

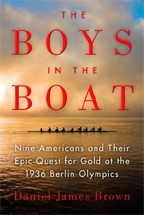

| Daniel James Brown's riveting

description of Washington's 1936 Olympic rowing victory in the NY Times

bestseller The Boys in the Boat - and his powerful narrative of the men

that lived it - has generated renewed interest in this remarkable story.

Below you will find a continuous collection of information; some of it

new, some of it originally compiled during the 2002-2003 Centennial season, but

all of it relating to the '36 team. For those of us fortunate enough to have rowed at Washington during our college years, the story of the these men is not far removed from many of the personal experiences shared since rowing first began on the shores of Lake Washington in 1903. For both the men and women of Washington, the shared experience of setting goals, and then striving to achieve them together, has created countless personal friendships that last lifetimes and cross generations. It has also led to great achievements on the water, some on a global stage like the '36 team, some on a local stage, but each one as important as the next. Every man and every woman who has ever picked up a white blade at Washington, and every experience wearing the "W", builds on what came before. More on the extensive history of Washington Rowing, sorted by decade and year, is here - The Washington Rowing History. |

![]()

![]()

When writing the men's 100-year history of Washington Rowing in 2002 and 2003, I had the honor of sitting down with many of the men who had contributed or participated in some of the more memorable rowing experiences at Washington.

I met with Bob Moch '36 on a number of

occasions to talk about his time as both a coxswain and a coach, from 1933 (the

year Washington won the first 2,000 meter National Championship), to his tenure

as UW frosh and lightweight coach at the end of the 30's. Our

conversations covered multiple topics, including his rowing career, stories of

stowing away in baggage cars, Al Ulbrickson and Tom Bolles, and driving coast to

coast in a brand new Packard.

I met with Bob Moch '36 on a number of

occasions to talk about his time as both a coxswain and a coach, from 1933 (the

year Washington won the first 2,000 meter National Championship), to his tenure

as UW frosh and lightweight coach at the end of the 30's. Our

conversations covered multiple topics, including his rowing career, stories of

stowing away in baggage cars, Al Ulbrickson and Tom Bolles, and driving coast to

coast in a brand new Packard.

I recently re-visited some of the cassette tapes I made of our interviews. Keep in mind these were intended as reference material for writing (the sound quality is not great), but it seems appropriate to get this first part published to hear one of the men who experienced the 1936 Olympic victory relate the story, a story that has been so well documented in Daniel James Brown's The Boys in the Boat.

Not all of our interviews were taped, but when we sat down in October of 2002, the topic was 1936 and the recorder was on. This conversation begins with the fall of 1935, how the crew came together, "LGB", the IRA's (coming back from many lengths down), the U.S. Trials, the Olympic final, his post-race travels and the beginning of his coaching career. You will want to be comfortable; this first part is 30+ minutes long: Washington Rowing: Bob Moch and the 1936 Season. Recorded with Eric Cohen, October 2002. mp3 format, 33:45

Want to learn more about The Boys in the Boat, the '36 crew, and how rowing in the 30's compares to today? GoHuskies has an interesting summary of the stats and figures showing how the sport has changed (and also stayed the same) - The Boys in the Boat: Then and Now. In addition, Columns Magazine published a short piece by Colby White, son of John White '38, recalling his father, here - Finding My Father. And of course, don't miss our history section - The 1930's, or coxswain Bob Moch '36 describing the Olympic race for us in 2002: Bob Moch, the '36 Olympics and the Influence of Husky Crew on His Life. Recorded with Eric Cohen, November 2002, mp3 format, 1:29

![]()

|

Rowing footage from Leni Riefenstahl's "Olympia", the innovative film documenting the 1936 summer Olympic games in Berlin. The start of the eights race begins at 1:09, but keep in mind this film was a stylized version of the events, as much a movie (and pre-war public relations) as it was a pure documentary. So interspersed in the actual race footage is film taken of the stroke oars and coxswains, including footage of Bob Moch and Don Hume that were shot days before the actual race with large film cameras mounted inside the shells. But the race itself, shot across the course with all crews involved, and the post race ceremony... that is all race-day footage. Watch the clip in entirety from the beginning and catch the German 4- winning the gold prior to the eights race, with the reaction of the German crowd at a fever pitch.

|

||||||||||

![]()

In

December of 1967, the men's rowing team from Pacific Lutheran University pulled

off one of the more unique boat transfers in the history of Northwest rowing,

and at the center of this adventure was the '36 Husky Clipper.

In

December of 1967, the men's rowing team from Pacific Lutheran University pulled

off one of the more unique boat transfers in the history of Northwest rowing,

and at the center of this adventure was the '36 Husky Clipper.

The University of Washington, and George Pocock himself, were the hub of rowing in the Pacific Northwest at the time. They, together, were an incubator for nascent rowing programs in the region. Greenlake Junior Crew in Seattle was one of the first (chartered in 1947), and would often be the recipient of no-cost hand-me-down shells from the UW. This was all done with the ethic of "grow the sport". In 1963, the Pacific Lutheran University (in Tacoma) rowing team was just starting, and needed an eight. The shell the UW delivered? The Husky Clipper.

In the fall of 1966, Steve Nord, the manager of the Husky Union Building (commonly known as the HUB, and the center of student life on the UW campus) reached out to PLU to ask if they would consider giving the Husky Clipper back to the UW to be displayed in the Husky Den as a tribute to the 1936 Olympic team. "The purpose of this project is to add to the decor and college tradition of the Husky Den, and in a greater sense the student union building..." Nord wrote in January of 1967, in correspondence with upper campus administrators, "... and exemplifies Washington's long standing dominance in this sport." Nord was the organizer behind the effort, gaining the cooperation of Chuck Alm (UW Rowing Stewards), Al Ulbrickson, Fil Leanderson, and numerous UW administrators.

His proposal was approved, and the deal with PLU went like this: we (the UW) will donate a shell to Greenlake if you will take the Loyal Shoudy from them (Greenlake), and give the Husky Clipper back to us. The UW truck arrived in April in Tacoma to pick up the now well-worn shell, where it was then transferred to a shop to be reconditioned and rehabilitated by Karl Stingl, a project that, due to thirty years of wear and tear, went beyond the two month timeline. “I know I probably let my aggressive interest in this project show to the point of annoyance," said Nord in a letter to Stingl in the summer of 1967. "[but] please accept my personnel expression of sincere gratitude for all the hard work you put into the shell to get it ready for display." Finally, on September 9, 1967, the Husky Clipper, in a formal ceremony, was hung from the rafters of the Husky Den, where it would remain until the remodel of the HUB in 1975.

But PLU was still in need of a replacement shell. Through various delays and logistical issues, the Loyal Shoudy was finally made available in the late fall of 1967, beginning an adventure that to this day remains one of the more remarkable in NW Rowing circles. Simply referred to as the "Rowdown", it is the story of the PLU team - a team with zero dollars to facilitate a transfer like this - driving up to Seattle on December 16, 1967, carrying the Loyal Shoudy on their shoulders from Greenlake to Lake Washington in the snow, rowing through the Chittenden locks and - amazingly - rowing her the 40+ miles, from pre-dawn to night, on the winter waters of Puget Sound to Tacoma. Bill Knight published the story in the Seattle Times as the team was celebrating their 50th anniversary in 2017, and it is here - The Rowdown - If You Loved Boys in the Boat, Don't Miss This Tale of Adventure.

Jim Ojala, the captain of the PLU team at the time, and also a collaborator with Stan Pocock on his book "Way Enough", reminisced on the adventure when we asked him about it:

"The Rowdown was a

once-in-a-lifetime event. Someone once said of it, 'it’s surely one of the

greatest rowing stories of all time. The audacity is breath-taking!' Of course

I agree with him, but then I am admittedly a bit biased. George Pocock once

told me something similar the first time we met. I remember his words exactly

to this day: “What you lads did is the greatest rowing story I’ve ever heard.”

If George said it, it must be so!"

"The Shoudy was the same 1940 Loyal Shoudy you mention. And yes, George

did build some amazingly sturdy boats. BTW, one of the reasons Pocock shells

seemed to weigh so much is because of their narrow gunwales, which

concentrated the weight load in small areas. Yes, they were heavy, but not as

heavy as some people imagine. And a shell like the Husky Clipper (and

the Loyal Shoudy) were a joy to row. They literally don’t make shells

like they used to, and something has been lost in the transition. Stan

lamented the change to me many times during the two years we spent working

together churning out “Way Enough!”

Added 6/16/17 by Eric Cohen. Thank you Paul Zuchowski, HUB historian, for the pre-Rowdown timeline and correspondence.

![]()

From the History section, the following is the original chapter, written in 2002, of the 1936 men's team. To read this chapter in context with the entire decade of the 30's, visit here: Washington Rowing History: The 1930's

1936

Building into the Olympic year, Ulbrickson now had ten years of coaching behind him. At his side was his '26 classmate and friend Tom Bolles, and at his other side was the quiet master, George Pocock. The combined rowing experience - as athletes or coaches - of these three men was unmatched anywhere in the country.

Ulbrickson trained the men hard. Gone was the internal animosity of 1935, although there is little doubt that the fevered competition from that year led to better oarsmanship a year later. Outside of the later events of 1936, Bob Moch remembers the intersquad time trials of 1935 as the best racing of his career - the most intense and competitive. By 1936, that intensity was re-channeled into a saying that became the motto of the crew: "LGB", meaning "Let's Go to Berlin", and a second meaning - "Let's Get Better".

The first test for this crew came in April on Lake Washington. The freshmen and JV won their races easily, and the varsity finished the sweep with a three length victory over California. Note: Watch a newsreel of the V8 event here, including a jam packed spectator train running along the now Burke-Gilman trail: Stock Footage - University of Washington beats California in a boat race in Seattle, Washington (no sound). (thank you Bob Koch)

Two months later all three crews were back in Poughkeepsie. The freshmen and JV's both defended their titles, but the varsity remained a question. In opposite fashion of the two years before, this time the crew was almost instantly behind, and settled at a stroke rate below 30 - the leading crews moving out to a multiple - at least five - length lead. There the Huskies remained through the balance of the course, methodically stroking a 28, the crews in front, including California and Navy, sitting on them. At a mile and a half, Washington turned on the power like a switch, raised the stroke to 34, and the shell lifted out of the water. "We took off...we just flew by them" says Bob Moch, almost as surprised today as he was decades ago to feel the unleashed power of this crew. The win completed the first ever sweep of the Poughkeepsie by a west coast crew - and was the first ever varsity win for Ulbrickson.

Moch reflects on a practice at night on the Hudson river with this crew prior to that race, a defining moment for the team. The crew had postponed an afternoon time trial on the course because it was so windy and rough, and had gone to a movie instead. On the water that night after it had calmed, he remembers "it was pitch black, the wind calmed down and after the time trial was over, we turned around and headed for the shellhouse...all three crews were together, we started out, just going 26, 27 - just going home - we got so far ahead of the other two crews we couldn't even hear them ... you couldn't hear anything... you couldn't hear anything except the oars going in the water...it'd be a 'zep' and that's all you could hear - the oarlock didn't even rattle on the release." A shared moment in rowing history that special crews experience - still to this day.

From Poughkeepsie the men traveled to Princeton New Jersey for the Olympic trials. On July 5th they met a polished Pennsylvania Club Crew, New York Club Crew, and Ky Ebright's California crew for the right to represent the country in the Olympics. Ulbrickson's now practiced strategy of "Keep the stroke down and then mow 'em down in the finishing sprints" was executed to the letter by his team, casting all three crews out for almost a full length while rowing a 34 before reeling them back in one by one. In the final 400 meters, the Huskies walked through the Pennsylvania crew as Hume took the stroke up to a forty, and they won by a length going away. "Hume stroked a perfect race and I think this crew will give a good account of itself in Berlin" said Ulbrickson.

The men stayed at the New York Athletic Club rowing quarters on Travers Island north of New York - with time for rest and rejuvenation - until departing with the entire Olympic Team for Hamburg aboard the S.S. Manhattan. George Pocock and members of the NYAC helped place the Husky Clipper onto the boat deck of the ship for safe transport to Europe.

Once in Germany, the team stayed near Lake Grunau, the site of the Olympic competition, at Koepenik. The team worked out twice a day on the lake, and dined at night with all of their competitors in the same mess hall. They also participated in the Opening Ceremonies, marching before Hitler and 120,000 frantic German fans, and attended some of the games.

The race format was similar to today. Three heats, with the winner advancing to the final, and a repechage (second chance for those not winning a heat), with the three top places of that race also advancing to the final. Washington won their heat against what Ulbrickson and Pocock felt would be the toughest competition, Great Britain, and in the course of doing it set a new world record. Germany and Italy won the other heats; these three crews now had two days of rest before the final.

And rest was important for Washington. Both Gordon Adam and Don Hume had contracted an illness earlier in the week. The effort during their prelim only exacerbated the symptoms, particularly Hume's. On the day of the final race, he was plainly ill - but Ulbrickson had made his decision. Much like Rusty Callow and Dow Walling at Poughkeepsie in1923, the alternative was not spoken that day. Hume would race.

The six crew final was in the afternoon. Washington was assigned lane six, based on the German officials' decision to position the slowest qualifiers in the most protected lanes (this was challenged by the Americans to no avail). The slowest qualifier was Germany, the second slowest was Italy. The starter faced into the quartering headwind, and his commands were unheard by the Huskies, who nevertheless got a decent start. Hume brought the stroke down to a 36, and the crew went on cruise for the first 1200 meters.

Germany, Italy, and Britain all moved ahead, with the leader, Germany, at least a length up. Fighting the quartering headwind in lane six, the Huskies began to increase the stroke rate. Finally, with about 500 meters left in the race the lakeshore changed, disrupting the lee in which Germany and Italy were racing. The quartering headwind was now evenly felt, at about the instant Hume and his crew began to sprint. By now we know what happens when this crew would sprint, and the confidence they had in each other; every race in 1936 this crew had fallen behind, only to gain it back. The last 200 meters were a blur, with Hume bringing the stroke rate up to an unheard of 44, the crowd chanting "Deutsch-land, Deutsch-land, Deutsch-land", and yet it was in that last 200 meters that the United States went from third to first, crossing the line about ten feet in front of Italy, with Germany third.

The exhausted crew rowed in front of the grandstand, then to the dock, where a wreath was placed over the head of each oarsman and the coxswain. There were no interviews. The men stayed in their quarters that night. The next day they received their medals in the Olympic stadium; after the games were over, they went home various ways, some choosing to travel Europe, others going straight home.

Historically speaking, the 1936 Washington crew would have been memorable without the Olympic victory. By sweeping the Hudson for the first time, the crew established itself as the deepest to date; with the varsity coming from lengths back in the last half mile, it established itself as one of the strongest.

But with the almost surreal Olympic victory in pre-war Germany, the crew became legendary. And although the story itself seems to have a life of it's own - every perspective is different, and the years blur some of the details - the fact remains that this is the first Husky eight-oared crew to complete their season as undefeated National Champions - and - World and Olympic champions. And forever will they hold that honor.

The 1936 Varsity Boat Club - note the house picture in the bottom right corner. Tyee photo.

1936 senior crew managers Bob Edwards and Bob Lund. Tyee photo.

Don Hume's sense of the boat and the men behind him was one of a kind. He was so ill in Berlin that Ulbrickson replaced him at workouts and seriously considered alternatives, but John White and Jim McMillin interceded and asked the coach to get Hume back in the boat. They said the rest of the men would pull him down the course if they could just have his rhythm back, to which Ulbrickson reportedly said "Well he doesn't pull anyway!". (1) Tyee photo.

"This crew was like a band of brothers" says Bob Moch

"each as vital and valuable as the other." Bow to stern, Morris,

Day, Adam, White, McMillin, Hunt, Rantz, Hume, Moch.

Husky Crew

Foundation photo: Erickson collection.

"This crew was like a band of brothers" says Bob Moch

"each as vital and valuable as the other." Bow to stern, Morris,

Day, Adam, White, McMillin, Hunt, Rantz, Hume, Moch.

Husky Crew

Foundation photo: Erickson collection.

Tom Bolles and Al Ulbrickson sporting Fedora hats and lots of W's in 1936 (literally and figuratively). Royal Brougham of the Seattle Post Intelligencer wrote of Ulbrickson watching the 1936 IRA varsity final: "...the finest crew he had ever coached seemed beaten beyond all doubt. When the tide of fortune suddenly changed, Tom Bolles pounded a stranger with his hat. The dignified George Pocock whooped (yet)... Al Ulbrickson's sphinx-like face never as much as quivered. Not a sound came from his lips." Tyee photo.

Bob Moch was varsity coxswain in 1935 and 1936, coached

the Washington freshmen and lightweights with Bud Raney from 1937 - 1939, then

spent five years at M.I.T as head coach. He also received the Schaller

Scholarship Plaque from 1934 through 1936 with the highest grades on the team,

and was VBC manager his senior year. Did he know about crew before he

entered college? "Oh - everybody did...I knew for years I was going to

turn out to see if I could be a coxswain for the University of Washington crew...I

was always interested in athletics and there was only one place I could go."

Bob describes the 1936 Olympic race, and what Husky Crew meant to him here -

Listen: Bob Moch and the 1936 Olympics. Tyee photo.

The 1936 varsity, left to right: Don Hume, Joe Rantz, George "Shorty" Hunt, Jim McMillin, John White, Gordy Adam, Charles Day, Roger Morris, cox Bob Moch in front. Only Moch was a senior. Tyee photo.

A postcard from the 1936 Olympic Games depicting the rowing course on Lake Grunau. Bob Moch says this is not the best representation: there were grandstands on the water side of the course but they only spanned the last 200 - 300 meters, not the full length. Most importantly though is the lack of topography; the promontory that shaded the inside lanes from the wind is not depicted, and played a large role in the way the final race played out. The postcard is dated Aug. 12, 1936, and reads partially - "En route to rowing prelims in S. Berlin. I hope to see U.W. crew in action - they're scheduled to row this afternoon...". If the writer made it to the races, he saw a new world record established by the Huskies. Husky Crew Foundation.

Washington defeating the British in their first heat by about a half length in world record time of 6:00.86 . The physical and mental effort expended in this race by the favored British likely ended their Olympic hopes; although advancing the next day through the repechage, they finished out of the medals in the final. Bob Moch Photo.

About 200 meters to go in the Olympic final. Italy is ahead by over half a length, with Washington (in the far lane) and Germany (in the near lane) both very close for second. Bob Moch Photo.

About a 100 meters later and Washington and Italy are close to even - that is how fast this crew moved when the stroke rate went up. Bob Moch Photo.

The finish. Tyee photo.

Moments before the Star-Spangled Banner. Bob Moch Photo.

Bob Moch's Olympic medal and certificate. The memories remain emotional to this day, and he says of the eight men in the crew - "my honest belief - I think they were the best rowing crew that ever existed". Husky Crew Foundation Photo.

Tom Bolles was the "professor type - very intelligent and had a wonderful personality" says Moch. 1936 was the last year Bolles coached at Washington - after the Olympics he was offered and accepted the head coaching position at Harvard. He coached there until retirement in 1951, and is credited with the resurgence of the Harvard program (his crews won the Harvard-Yale race in all but two of the years he coached). Tyee photo.

Events of the Century -

is the article from the December 29th, 1999

Seattle Post-Intelligencer naming the 1936 Olympic victory as the greatest

Seattle sports moment of the 20th century. Some of the story is

a bit embellished - there is no other record of the team ever meeting Hitler - but the story is accurate from the personal perspective

of these athletes; after the race they were,

for a man, so physically and emotionally exhausted it was likely impossible to

remember the race and post-race details a week later - let alone sixty-three years

later when this

article was written. Although various perspectives may differ - what crew

wouldn't - it certainly catches the electricity of the moment so many years ago.

1) "Way Enough", Recollections of a Life in Rowing; Stan Pocock; pg. 33-34.

| Home | Contact Us | © 2001 - 2023 Washington Rowing Foundation |